Aristotle's famous discussion about friendship occurs in Nicomachean Ethics books 8 and 9. What presenters typically draw from his inquiry tends to be restricted to a few topics: the nature of friendship itself, the three main types of friendship, and the three values associated with those types (virtue, pleasure, and usefulness). His treatment of "friendship" - or really, better expressed, relationships - has much more to offer, however, and one particularly important topic is how relationships break down.

Why do people stop feeling mutual affection? Why do they cease to desire good for the other person for their own sake? Why do they begin to complain, feel resentful, or cut back their own involvement in the relationship? Aristotle doesn't examine every possible reason - how could he? - but he does set out some generally applicable guidelines that remain relevant to relationships in the present.

Among these is the need to pay proper attention to imbalances within relationships. Does one person bring more to the table than the other? Do the partners change in themselves, or in what they provide to the other person, over the course of time? Do desires and expectations change as well - and are these changes noticed, communicated, and dealt with effectively? If not - and particularly when the relationship is on shakier grounds than the partners would like to believe - then it is reasonable, though sometimes lamentable, that the relationship breaks down.

One red flag, which Aristotle touches upon, but doesn't explore as much as one might like, is when the "friends" have markedly different understandings of what their relationship is about. They might also differ over what goods the friends are providing or producing for each other, what needs ought to be met, and where the limits or boundaries are. This can be particularly problematic when these differences of basic viewpoint remain unarticulated, or even unsuspected. But even when they are right out in the open, these differences can gradually erode the relationship, if one of the partners - rightly or wrongly - is unwilling to accept the other person's version of the relationship.

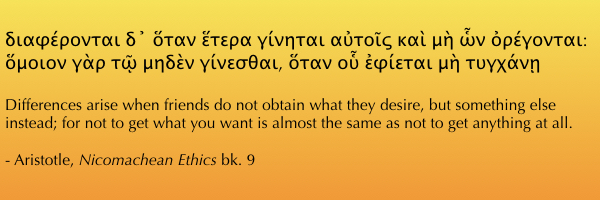

A closely connected problem is highlighted by the passage quoted above. Getting something "different" or "other" than what one actually desires in some respects feels worse than simply getting nothing. And when that comes from a person partnered to you in a relationship - whether romantic, familial, friendship, business, or even just social - it sends a message: that person doesn't really desire you to enjoy the good you do desire.

It ends up producing even more disappointment, sadness, anger - even anxiety - when the person doing the giving insists, for example, that what he or she gives is really what you deserve or ought to have. Or that what you desire and perhaps even explicitly ask for isn't as good as what they decide to give. All of us can recall times this has happened to us. Now with that in mind, consider whether we haven't also engaged in this sort of substitution with others in our relationships.

No comments:

Post a Comment